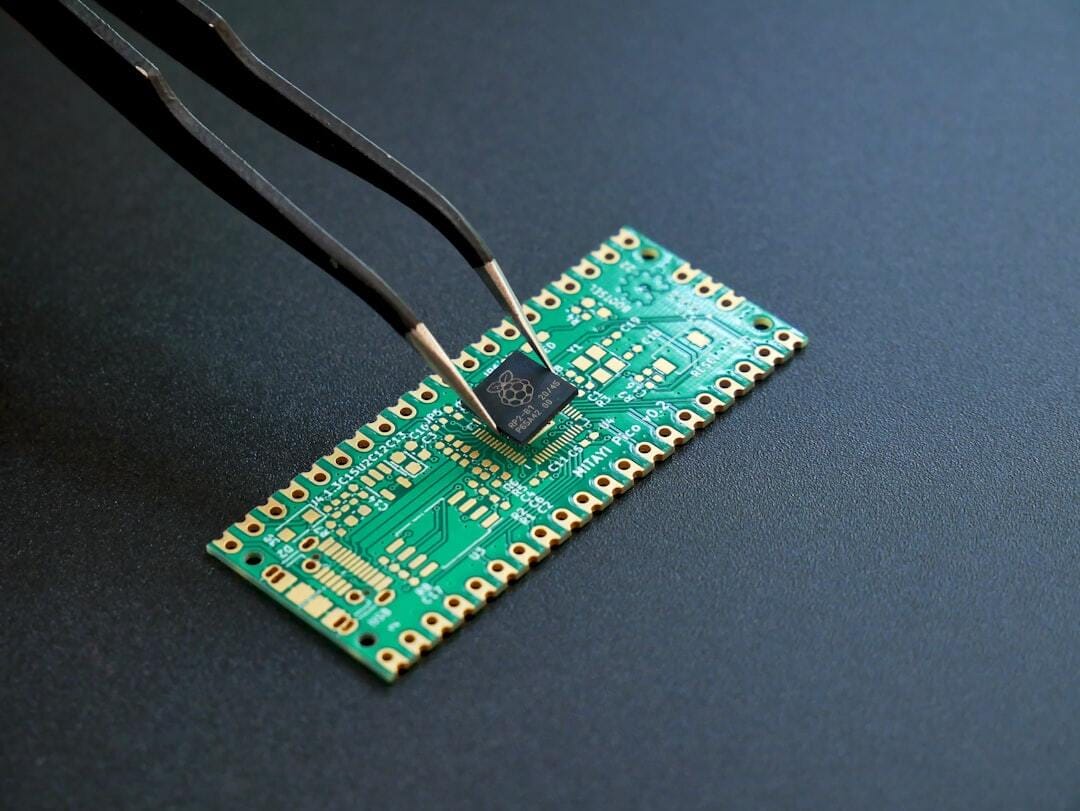

In the old world, power was measured in barrels and battleships. In the new one, it’s measured in nanometers.

Semiconductors — once the invisible enablers of progress — are now the frontline of global economic and geopolitical rivalry. From Washington to Beijing, Tokyo to Brussels, governments are no longer treating chips as consumer goods but as national assets.

The global semiconductor industry, valued at roughly $600 billion, is projected to surpass $1 trillion by 2030, according to major industry forecasts. Yet behind that growth lies a deeper anxiety: control. The world’s most advanced chips are overwhelmingly produced by a single firm — Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) — which holds over 70% of global foundry market share and dominates leading-edge production (7 nm and below). Taiwan’s geographic position, at the center of U.S.–China tensions, has turned its fabs from industrial marvels into geopolitical fault lines.

The United States, after decades of outsourcing, is racing to rebuild its domestic capacity. The CHIPS and Science Act, providing more than $50 billion in incentives, has spurred companies like TSMC, Intel, and Samsung to expand fabrication in Arizona, Texas, and New York. But the costs are staggering. Complex supply chains, engineering shortages, and permitting delays have pushed project budgets into the tens of billions — a reminder that industrial sovereignty is expensive and slow to achieve.

China, meanwhile, is accelerating efforts to reduce dependence on Western technology. After successive rounds of U.S. export controls on advanced lithography tools, Beijing doubled down on domestic innovation. Its flagship foundry, SMIC, has reportedly achieved 5 nm-class chip production using deep ultraviolet (DUV) lithography and multi-patterning — a notable technological milestone, though yields and production volumes remain uncertain. The achievement underscores Beijing’s strategic resolve to build an ecosystem resilient to sanctions and capable of supplying its vast internal market.

Japan, South Korea, and the European Union are pursuing parallel ambitions. Tokyo’s Rapidus consortium aims to mass-produce 2 nm chips before the decade’s end, supported by state subsidies and alliances with IBM. Seoul continues to expand its “K-Semiconductor Belt,” with Samsung and SK Hynix investing heavily in next-generation memory and logic technologies. Europe, seeking “strategic autonomy,” has pledged tens of billions in subsidies through the EU Chips Act, led by Germany’s Infineon and the Netherlands’ ASML.

Together, these moves signal a decisive shift: the era of a globalized chip supply chain is giving way to a world of regional fortresses — each blending industrial policy with national security.

Closing Takeaway (Strategic Lens)

For investors, this realignment has profound implications. Semiconductor capital expenditure now influences inflation dynamics, energy demand, and defense planning. Chips have become the backbone of everything from electric vehicles to AI data centers, and every new fab represents not just an industrial bet, but a strategic declaration.

The semiconductor race is no longer about technological speed alone — it’s about sovereignty. As nations compete to secure the supply chain of the digital age, the invisible hand of the market is yielding to the visible hand of the state.

The world once believed that globalization would make technology borderless. It now realizes that control of silicon means control of the future.

The semiconductor map of 2025 mirrors a divided world — one driven not just by efficiency, but by power, protection, and policy. And in that world, the question is no longer who can make the fastest chip, but who controls the means of making them.